After the frenzied sales of 2013, New York City’s real estate market didn’t miss a beat in 2014 — though its pace showed signs of stabilizing, even as prices reached new heights.

Despite the overall market’s widely-described return to “normal,” the co-op market saw its record for the priciest residential sale toppled three times: In September, hedge-fund manager Israel Englander paid $71.3 million for a duplex co-op at 740 Park Avenue, on the heels of the $70 million sale of the late Edgar Bronfman’s penthouse at 960 Fifth Avenue to Egyptian billionaire Nassef Sawiris. They were both outdone less than a month later, when billionaire Leonard Blavatnik dropped $80 million for the unit at 834 Fifth Avenue owned by New York Jets owner Woody Johnson.

It’s no surprise then that there’s more luxury housing coming, as developers race to complete condo towers for the super elite on 57th Street, which has come to be known as “Billionarie’s Row,” while other developments both in Midtown and Downtown reach for the sky, in both price and height. And there are several mega-developments on the rise, from Hudson Yards to South Street Seaport to Astoria Cove. But what else can the industry expect in 2015?

In this last issue of the year, The Real Deal takes a look at key topics and trends that will shape the market in the next.

Year of the premiere

With construction underway citywide, and particularly in neighborhoods like Downtown and the 57th Street corridor, 2015 is poised to see double the amount of new development launches, compared with 2014.

There are 6,287 condos set to launch in 2015, compared with 3,112 in 2014, according to data obtained from Corcoran Sunshine.

Because of the high cost of land and rising construction prices, the luxury sector is poised to see the lion’s share of the attention, though demand for one- and two-bedroom units is higher than ever.

“The next step is trying to navigate and deliver something that’s not super luxury,” said Jonathan Miller, president of real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel. “I think you’ll see more expansion into the lower-upper [end of the market] than what we’ve seen. The demand is extremely high, it’s just hard for the product to be created because of the cost of development.”

In recent months, concerns about a potential glut of inventory at the top of the market have gained more followers. But not everyone agrees.

“I still feel very bullish on the market,” said Susan De França, president and CEO of Douglas Elliman New Development Marketing. Through its partnership with London-based Knight Frank, she said Elliman has its finger on the pulse of the international market. “We still see a real, real strong, deep-rooted demand internationally to purchase in New York City.”

Boutique boom

Condo developers are bringing a crop of boutique buildings to the market, each crafted with a level of attention and care aimed at drawing discerning buyers.

The trend has already started to take hold.

Soo Chan’s 515 West 29th Street is

one of the boutique condos opening

in 2015.

In November, for example, Rome-based Sorgente Group’s 60 White Street launched in Tribeca with eight units, including a 3,078-square-foot penthouse that’s asking $9.265 million. And in September, architecture and development firm Flank launched sales at the six-unit 224 Mulberry Street, selling two condos for upwards of $3,330 per square foot within weeks. A 3,167-square-foot condo asking $10.75 million and a 3,392-square-foot condo asking $11.25 million were put under contract in mid-November.

Then there’s developer Edward Minskoff’s conversion at 37 East 12 Street in Greenwich Village, which launched in November, where the six units are priced from $9 million to $32 million.

According to Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group, 91 properties were set to hit the Manhattan market in 2014, with an average of 37 units each. That compares with 18 properties launched in 2010, with an average of 84 units per property.

In 2015, several more boutique buildings are set to launch, including Bauhouse Group’s 12-unit building at 515 West 29th Street designed by Soo Chan and an eight-unit building at 559 West 23rd Street that’s being developed by NY8 Properties LLC.

“I think the new luxury is boutique buildings,” said Douglas Elliman’s Frances Katzen, the exclusive broker for 60 White Street.

Even as smaller buildings proliferate, some developers are coming up with more “efficient” luxury condos — meaning tight-cut units that offer more bang for the buck —such as 15 Leonard. There, four-bedroom units measuring 2,621 square feet went into contract for prices ranging from $6.5 million to $7 million, according to Wendy Maitland, director of sales at Town Residential, which marketed the property.

The Karl Fischer-designed condos at 432 West 52nd Street also have efficient units, including a 436-square-foot studio for $610,000, or $1,399 per square foot; a 640-square-foot one-bedroom for $995,000, or $1,554 per square foot; and a 1,189-square-foot two-bedroom for $1.6 million, or $1,345 per square foot.

“It’s important that you have a myriad of product in New York, because there are a myriad of people,” said Elizabeth Ann Stribling-Kivlan, president of luxury brokerage Stribling & Associates.

To be sure, the new development market is still seeing larger residences than are typically available in the resale market.

During the third quarter, the average size of a resale unit was 2,675 square feet, compared with an average size of 4,364 square feet among new developments.

“Everything is cyclical. Three to five years ago, there was a dearth of grand-proportioned product,” said Maitland. “Now that the market is being much better served, there’s a tremendous opportunity in building more efficiently.”

And then there are bespoke residences.

45 East 22nd Street

At Bruce Eichner’s and Continuum Company’s 45 East 22nd Street, for instance, would-be buyers of the 83 condo units can choose from three wood finishes for the kitchen flooring and cabinetry.

“Choice in the past has been a complete no-no,” said Leonard Steinberg, president of tech-focused brokerage Urban Compass. “People like the idea of having their own personal choices.”

Others see the market leaning toward “beautiful structures with really functional layouts,” said Stephen Kliegerman, president of Halstead Property Development Marketing.

“I see a more competitive market in the $10 million and up” category, said Town’s Maitland. “There’s going to be a lot of attention paid to the architecture and design and the quality, more than ever.”

Price pop?

The average sale price in Manhattan for all kinds of residential properties jumped 18 percent from last year during the third quarter, to $1.68 million. Price appreciation in the luxury market was even steeper: The average sale price in the that segment increased 34 percent, to $7.25 million during the third quarter, according to data from Miller Samuel.

Diane Ramirez, president of Halstead Property, said at a recent REBNY luncheon that the 18 percent increase was “hard for buyers to absorb.Whether price appreciation will continue at the same clip is a source of debate.

“Right now, we’re at a point in pricing where it’s going to level off,” she said. “New development condo prices have risen 60 percent in the last two years. You can’t sustain those kind of price increases without leveling off.”

Beyond sticker shock, others noted that increased inventory levels have prompted the market to stabilize. “Now that developers, as well as brokers and customers alike, see there’s more in the pipeline, I believe there’s less of a fervor of price appreciation,” said Elliman’s De França.

During the third quarter, the listing inventory in Manhattan jumped 27.6 percent year over year to 5,828, according to Miller Samuel. Meanwhile, the number of sales dropped 13.3 percent to 3,328.

Miller said he thinks prices will continue to rise — a function of fewer sales than the frenzy of 2013 and still-low inventory levels. “We’re going to see some continued rise in inventory, but still far short of equilibrium,” he said. “There’s just been very little new product to date that has been outside of the high-end market.”

Maitland said she expects prices in the luxury market to continue their upward trajectory, because “there’s a larger demographic of buyers who are looking in that range and spending in that range than ever before.” (The “luxury” market is generally defined as the top 10 percent of the market in terms of price.)

Kathy Braddock, managing director of brokerage William Raveis NYC, noted that buyers from Russia, China and Brazil are still looking to move their money out of those countries. Among those buyers, there’s a continued appetite for trophy apartments. “There’s an underlying reason why these trophy apartments will sell,” she said. Investors “are trying to diversify their assets because of the global picture.”

Interest rate increase

Interest rates are still at record lows, but it’s widely believed a rate increase is coming in 2015. And while Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen hasn’t indicated when, economists point to sometime in mid-June.

That prediction means the next six months are likely to be busy.

“People are doing deals now as opposed to six months from now, because there’s more certainty,” said Jay Neveloff, a partner at the law firm Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel. “No one has a crystal ball,” he said, but everyone realizes rates are at record lows.

Among residential buyers, De França said an interest rate change would mainly impact first-time buyers, rather than the luxury market. That’s because in New York City, many luxury sales are all-cash, or a significant amount of cash.

Many of those all-cash sales involve foreign investors, who are expected to continue parking their money in New York real estate.

“The financial-crisis hangover is still with us,” said Miller. “Investors are wary of financial market investing. They’ve shifted to hard assets.”

He said investors snapping up New York City real estate aren’t necessarily looking to make money. “The primary goal is safety, capital preservation. We’re building the world’s most expensive bank safety deposit box. That’s what some of these buildings will end up being.”

Another group that would likely be hard-hit by rate hikes are developers themselves.

“It’s going to scare some [developers] away, because of the amount of equity that needs to go into these deals,” said Richard Wood, president and CEO of Plaza Construction. He said higher interest rates would prompt developers to set tighter schedules for contractors, in order to maintain profitability. “Developers or investors are now going to have a lot more risk of losing their investment, because a higher interest rate could suck the profitability out of a job if it’s not kept on schedule.”

While rising interest rates won’t impact the super high-end buyers or foreign investment, they are likely to slow mid-range condo sales, Wood said. “If something trips the market — maybe interest rates — developers will be holding the bag on a huge equity slug that could end up being lost, or they will have to try to wait it out.”

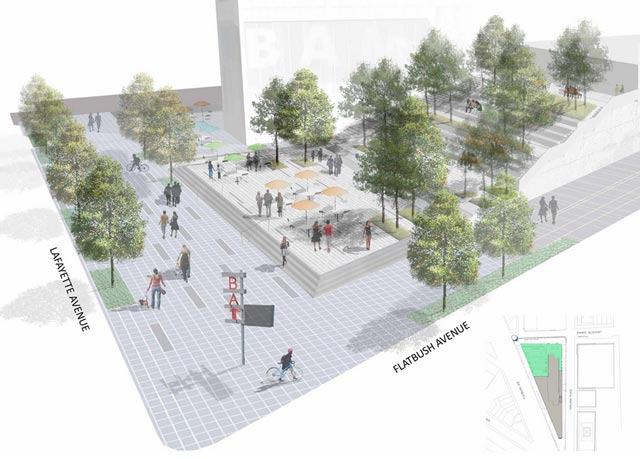

Astoria Cove is one of the developments where Mayor Bill de Blasio has marked a victory in his efforts to expand affordable housing in NYC.

Affordable housing

Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014 promising to address New York City’s lack of affordable housing. While details are still sketchy, 2015 could see some of the administration’s proposals implemented, in an attempt to move toward its stated goal of creating or preserving 200,000 affordable units in the next decade.

The mayor has had a few victories so far, including an agreement with Two Trees Development to increase the number of affordable units at the Domino Sugar factory site in Brooklyn, to 700 out of 2,300 units overall. In November, the city claimed another victory related to the 1,700-unit Astoria Cove project after reaching a deal with developer Alma Realty to make 27 percent of the units affordable.

To date, the mayor’s office has floated several concepts to ramp up the affordable housing agenda, including new mandatory inclusionary policies in new development and a possible expansion of the existing mansion tax, a 1 percent tax on sales over $1 million that generated $259 million in fiscal 2013. If 0.5 percent was added to transactions over $5 million, the tax would generate another $34 million in 2015 that could be directed to affordable housing.

Air rights may be in play to boost affordable housing, as well, after the Economic Development Corporation issued a request for proposals that offers free development rights on three city-owned lots in Long Island City, in exchange for permanently affordable housing.

“I think the city will continue to use every opportunity to support and expand affordable housing,” Neveloff said. “The mayor has made it clear it’s a priority in his administration [and] in their dealings, they are making that clear to the market.” Developers are factoring it in, he said. “It’s the new reality.”

Winston Fisher, a principal at Fisher Brothers, said that like every other operator and developer, his family’s company is watching to see what affordable housing policies take root. “You want affordable housing, and you want something that’s thoughtful and reasonable that doesn’t stifle growth, doesn’t stifle the market. The ripple effect can be profound.”

Will it be Queens’ turn?

As developers pushed farther into Brooklyn over the past decade, Queens has similarly seen some development in Long Island City and Astoria. But large swaths of the borough remain untapped.

At least until now. Some in the industry think Queens will grab the spotlight in 2015.

Even white-glove Manhattan brokerage firms are taking note.

“There’s only so far you can go into Brooklyn. I think Queens is next,” said Stribling-Kivlan of Stribling & Associates. “You want the best Chinese food in New York? Get out to Flushing. There are some really cool neighborhoods, not just Long Island City and Astoria.”

Increasingly, Kivlan said, she has buyers asking for Queens. “Queens is an incredibly established borough, but I think we’re going to start seeing some new stuff come out there,” she said, particularly since the commute to Midtown from some areas is just 15 minutes. “Queens reminds me of Manhattan 25 or 30 years ago, where you see an incredible amount of diversity and you get a lot of space out there,” she said.

To be sure, Queens’ development historically has been a step behind Brooklyn.

“It’s always been ‘Queens next,’” said Fisher, who noted the waterfront has seen a huge amount of development. “Is there organized development that can occur inland from that?” he pondered. “Good question.”

Braddock, meanwhile, described a “seismic shift” in where buyers are searching for homes. “Their first choice is not the island of Manhattan.”

She said by shifting to the outer boroughs, average New Yorkers are able to find more affordable housing.

In fact, high prices in Manhattan are already spurring more rental developments in the “outer outer boroughs,” according to a report from marketing firm Nancy Packes Inc.

For example, Brooklyn has roughly 21,500 rental units in the development pipeline, including 13,025 units in neighborhoods outside the “core” areas of Brooklyn Heights, Downtown Brooklyn, Williamsburg and Dumbo.

In Queens, there are 11,980 units in the pipeline in “core” neighborhoods, which include Hunters Point, Long Island City and Astoria, plus another 3,281 units in the pipeline in other communities in the borough.

Brokerage scene

Following a year that saw top brokers Leonard Steinberg and Kyle Blackmon join startup firm Urban Compass, 2015 is poised to see even more fallout among firms as new companies join the fray.

According to Braddock, buyers check StreetEasy before logging onto any of the firms’ websites. In 2014, industry veterans Braddock and Paul Purcell launched a New York City office for Connecticut-based brokerage William Raveis. “The landscape looks different,” Braddock said. “I think that companies like ours and all the others are making the brokers in more of the established firms look at themselves and say, ‘Gee, could I be doing my business differently?’”

“The biggest mousetrap is StreetEasy. You can be your own broker today, and have the same power, to some extent, that a Corcoran or Douglas Elliman has.”

Consolidation among brokerage houses also has changed the landscape, she noted. Publicly-traded Realogy owns Corcoran Group, Citi Habitats and Sotheby’s International, while Vector Group owns Douglas Elliman, and Terra Holdings is the parent company of Brown Harris Stevens and Halstead Property.

At public companies, Braddock noted, “You have to make a profit. People expect to see certain things. As a private company, you have more flexibility.”

Julia Hoagland, an agent who joined Urban Compass from Brown Harris Stevens in November, said her decision was shaped by a desire to help build a new kind of brokerage. “I really believe in the vision that Urban Compass has, and that they’re going to change the way New York City real estate works by leveraging technology,” she said.

REBNY’s executive search

Although Steven Spinola, president of the Real Estate Board of New York, doesn’t plan to step down until the end of 2015, the search is on for his successor, who will be named in the next few months.

REBNY president Steven Spinola

Spinola’s intention to retire from REBNY’s top post, a job he’s held since 1986, was first disclosed in June. A search committee led by REBNY Chairman Rob Speyer is leading the charge to find a replacement — no small feat considering Spinola’s name has been synonymous with REBNY’s for nearly three decades. The real estate industry is also facing a particularly uncertain political climate, given that the de Blasio administration is perceived by some as less business- and developer-friendly than the Bloomberg administration was.

The trade group is one of the state’s biggest lobbying groups and Spinola’s successor is likely to be someone skilled at working with city officials and simultaneously representing the interests of the real estate sector.

This fall, several names were floated as potential candidates for the post, including John Banks, vice president of government relations at Consolidated Edison, who is reportedly the front-runner for the job. “We will make an announcement when the search process has concluded,” REBNY spokesman Jamie McShane said in a statement.

Other contenders are Jim Whelan, senior vice president of public affairs at REBNY who has helped lead REBNY’s lobbying efforts for the past four years, and Ramon Martinez, deputy chief of staff for Melissa Mark-Viverito, City Council speaker.